Have you herd this one?

Charles MacInnes

Charles MacInnes

The start of my professional career was a wild goose chase. From 1958 to 1973 I studied the small Canada Geese that nested near Kuugjuaarjuk, south of the settlement of Arviat, where that river runs into the western side of Hudson Bay. 1963 was a big year, I finished my PhD and married my grad school sweetheart. On our honeymoon we drove west, and one stop was a visit to my aunt and uncle on the a7 ranche, west of Nanton, Alberta. John was my father’s cousin, Eleanor my mother’s sister. They had imported two Cardigan Welsh Corgis from Britain, the first in Canada, and Kaye and I fell in love with Wyn and Winkie, so we booked a puppy from their next litter. I was an avid hunter back then, so we also bought a Norwegian Elkhound puppy. Finn and Dai joined our household in 1964, and were fast friends all their lives.

Dai was a character from day one. He was small by show standards, but very well-muscled, and extraordinarily intelligent. He considered himself the world’s finest ball-player. As a puppy, he learned to retrieve a thrown ball, come back to the thrower, put the ball down, and roll it up to the human’s feet with his nose. If you were slow to pick it up, he would sit up to beg you to get on with the game. I did not teach him how to play, he taught me! He often caught the bouncing ball with a big leap. In the spring of 1965, we flew north. Kaye had decided to do her PhD on plant ecology in the north, so we had to bring the dogs. After our chartered Norseman landed on the sea ice in front of the village of Arviat, and we had unloaded all our gear and supplies for the summer, he sniffed each backpack until he found the pocket full of balls. He sat up and looked at me, so I threw a ball for him. I treasure the memory of him entertaining a lineup of fifty plus Inuit They quickly set rules for the game: each individual got one throw, and then went to the back of the line. They kept him running for a full two hours.

Dai quickly adapted to camp life. Early one morning, he climbed out of the foot of my sleeping bag but, most unusually, did not rush out the tent flap barking. Instead, he stood back from the front flap and gave a very menacing growl. As I got up, he and Finn rushed out, barking fiercely. When I looked out the front tent flap, they were chasing a polar bear down the river bank, and, there on the flap was a huge muddy footprint. During nesting season, I walked up to twenty miles a day, finding and checking goose nests. Dai came with me: that required not only running, but a lot of swimming, as the geese nested on small islands in the shallow pond all over the tundra, so no wonder he was very fit.

Soon after the goslings hatch, adult geese molt all their wing feathers, and so are flightless while they grow a new set. Is it coincidence that they fly again just as the young have grown up enough to learn to fly? The four weeks they were flightless made them easy to round up for banding. Our normal procedure was for four or more men to go upstream, far from the river, two on each side. We kept in touch by radio. When we were far enough upstream, we would close in on the river, one man to each bank, and the others a quarter mile inland. The geese naturally fled to the river when they saw us, so we could close in on them, and herd the flock to the banding pen. That enclosure, made of chicken wire, had a large holding area, and a smaller pen, which we called the banding corner. We could catch as many as 300 Canada Geese per drive, and several hundred Snow Geese, which I banded for the Canadiann Wildlife Service, who funded my whole project.

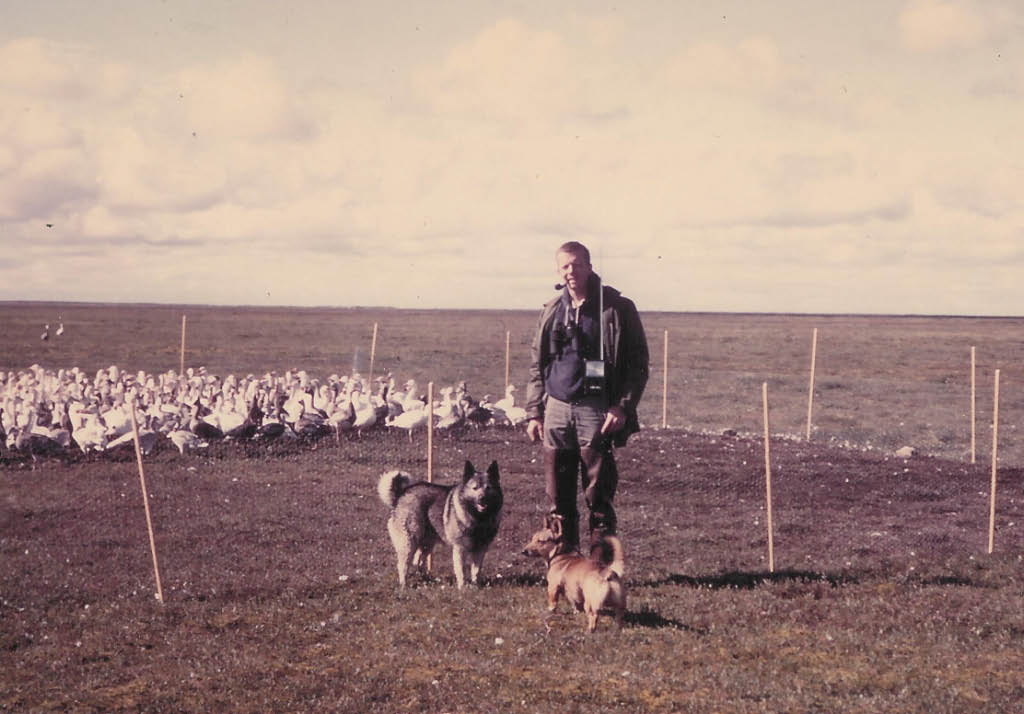

On the first drive of the 1965 season, Dai Morgan came with me. By the time we had the geese in the big pen, and were cutting out the first group of twenty or less to move them into the banding corner, he had the situation sized up. He amazed me: without any training he showed that he could herd geese. In the larger pen, he quickly went around behind the big flock and brought them to me. I learned to walk into the banding corner, and close the gate as soon as he had pushed 20 +\- birds into it. I was new enough to the dog world that I did not know what commands to give, and Dai showed me that none were needed. My grad students really admired his ability.

Charlie MacInnes banding geese with dogs Dai Morgan and Finn